1,000,000 died in 100 days of slaughter. How Rwanda still bears the scars of genocide 30 years on

First published on Metro

Reports found that nearly 100,000 children were orphaned during the genocide. May 25, 1994. (Picture: by Scott Peterson/Liaison)

In early April 1994, as the wet season left morning raindrops on the bright green leaves that cover the endless hills of Rwanda, millions woke up to a country that would be changed, horrifyingly, for ever.

In less than 100 days, almost a million Rwandans – mostly from the Tutsi minority group – had been brutally murdered.

Rwanda, the small, landlocked country in central Africa, was historically composed of various socio-economic groups, the largest being Hutu (85% of the population), and Tutsi (15%). Under Belgian colonial rule in an effort to divide the population, Rwandans were handed identity cards which turned the groups racial, with the Belgians favouring the Tutsi. Tensions and resentment between the groups began to take root and would cause outbreaks of violence for decades after.

On the 6th April 1994, hours after the Rwandan president’s plane was shot out of the sky, thousands of extremist Hutus – spurred on by propaganda decades in the making – began to torture and kill the Tutsis and moderate Hutus who lived alongside them.

Neighbours murdered neighbours, husbands murdered wives. Children were forced to kill their loved ones before they themselves were killed. Many were burnt alive.

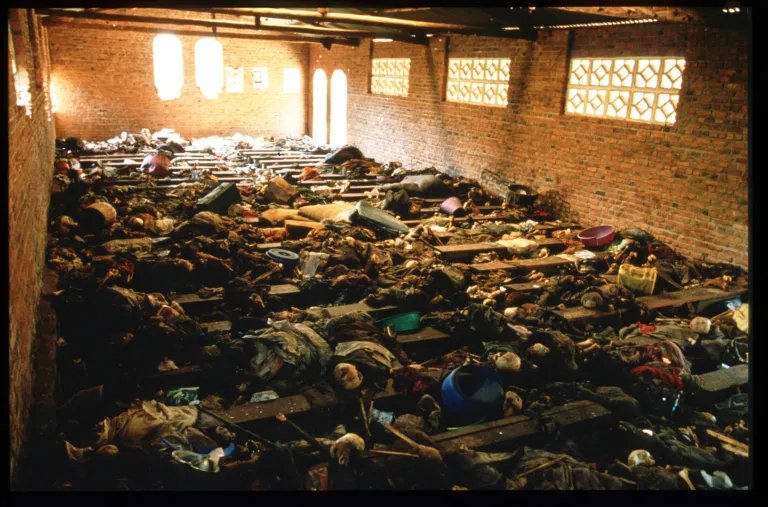

Many thousands sought refuge in churches, where some pastors informed the Hutu militias leading to grenades being thrown in, killing hundreds at once. Those who survived were hacked to death.

Women were deliberately infected with HIV through rape by freed AIDS patients, leading to thousands of deaths, and many more who are still living with AIDS today.

The horror that so many experienced was unspeakable.

One of the worst single massacre sites of the Rwandan genocide, Rukara saw 800 people die inside and around a church (Photo by Scott Peterson/Liaison via Getty Images)

The remains of murdered Tutsis lie on the floor of a church in Ntarama, Rwanda, September 1994 (Picture: Scott Peterson/Liaison via Getty Images)

And yet, it is not in mass bloodshed where Rwanda’s story ends.

Today it ranks as one of the safest countries in the world. It is leading Africa with its technological developments, takes in refugees from all across the world and was the first country to have a female majority in parliament.

Many who took part in the killing live freely among survivors today, something many considered impossible 30 years ago.

The shadows of Rwanda’s horrific recent past are still there and the wounds still cut deep, as all Rwandan citizens carry the scars, memories and consequences of 1994 with them.

But Rwanda’s progress and transformation from a broken to a striving country in just three decades has been astonishing. This is its story.

Memories of 1994

I’m sitting down with Freddy Mutanguha, the director of the Kigali Genocide Memorial on a warm March morning. Freddy, with his open-collar shirt and kind expressions, is a man who exudes a stoic calmness. He is someone who listens intently when someone is talking, and pauses before he speaks himself as if choosing his words carefully.

“There has been a lot of change to make the country what it is like today.” Freddy Mutanguha, Director of the Kigali Genocide Memorial (Picture: Jeremy Ullmann)

‘We grew up with discrimination’, Freddy says. ‘My parents first met in a refugee camp, and my mother would tell me that since 1959 the Tutsi people were denied rights. I saw it myself, teachers enforced government propaganda, telling the Tutsi in my class how we were the enemy, snakes, liars. Words to dehumanise the Tutsi.’

‘When the genocide began, my mother was convinced that women would be spared, so she told me (the only male child in our family) to hide with our neighbour Peter, a Hutu and a friend from my school.’

‘On the 14th April, they attacked my house. One of my sisters ran away and escaped. I found out later that my parents were taken before they were killed with machetes and clubs. I found their bodies years after, their skulls crushed in many places.’

‘The rest of my sisters were thrown alive into a long septic tank, where the men then threw stones down at their heads until they died. I could hear their screaming voices from Peter’s house where I was hiding. These voices will never leave my mind.’

Freddy’s experience is far from rare in Rwanda. Almost everybody you meet, from the restaurant waiter to the scores of moto taxi drivers filing the busy streets with traffic noise are likely to have lost multiple relatives, or had relatives who took part in the killing.

Victim photos from Kigali Genocide Memorial (Picture: Jeremy Ullmann / Kigali Genocide Memorial)

Jeanne Mukankuranga, who was born to a Tutsi mother and a Hutu father, was 20 at the time of the genocide. She explains how she and her family – including her 6 month old son – had to hide within tall crops as the Hutu extremists searched her village for Tutsis.

She said: ‘We were so scared that they would think we were Tutsi, because my grandfather was tall and slim. It didn’t matter that his identity card would say he was a Hutu, they would not have believed it.’

‘When we watched them from the crops, every time my baby started to cry I was terrified we would be found. I felt in that moment that I had lost my humanity. I kept thinking – please God, help me survive this day.’

Jeanne was not caught, but her mother’s family were all murdered except for one relative. She says, softly, that the images of genocide – including the piles of bodies left on the roadside that she had to walk past with her baby in her arms – will always stay with her.

Beatha Uwazaninka was 14 and was visiting her uncle in Kigali for the Easter holidays when the killings began.

She said: ‘The only reason I wasn’t killed was because I wasn’t counted for. You need to understand that the genocide was not something that came out of the blue, it was planned, they had a list of names for each house. When they came to my uncle’s house and murdered him and his family, I ran and hid with a neighbour, Mama Mohammad.’

‘Over the next few months, because nobody knew who I was, I was sent out to collect provisions. Every time I left the house, to return alive was due to a collection of divine blessings, as I had to avoid the killers, or I had to convince people that I was Hutu.’

‘One day at the market – which was continuing to run as normal for those not targeted – a woman recognised me and called out my nickname. She said that my mother had been taken to be drowned – that’s how I discovered my mother and family had been murdered. I couldn’t even look up as I didn’t want to draw attention to myself. I walked away, not able to accept that it was true.’

The Children of Genocide

Nowhere were the affects of that horror more traumatising and consequential, as through the eyes of the children survivors of genocide. A Unicef report in 2004 estimated that nearly 100,000 children were orphaned during the 100 days in 1994, and 70% of Rwandan children witnessed someone being killed or injured. It is extremely common to meet 30-40 years olds today and hear similar stories.

Reports found that nearly 100,000 children were orphaned during the genocide. May 25, 1994. (Picture: by Scott Peterson/Liaison)

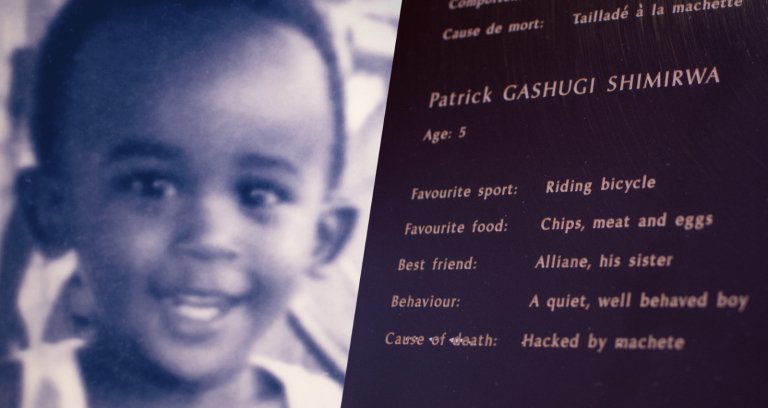

In an attempt to exterminate the Tutsi line, hundreds of thousands of children were also murdered, and there is a room in the Kigali Genocide Memorial dedicated to them. It is a haunting and emotional experience seeing the enlarged photographs of young lives cut short, the innocence in their eyes staring right at you, with a small plaque detailing the games they had loved to play, who their best friend was, their favourite food. The last line, a short line, simply saying how they were killed.

The haunting ‘Children’s Room’ (Picture: Jeremy Ullmann / Kigali Genocide Memorial)

‘Hacked by machete’ was a common cause of death (Picture: Jeremy Ullmann / Kigali Genocide Memorial)

Justice

Not long after the Rwandan Patriotic Front captured Kigali which ended the genocide, Freddy – among many others – volunteered to go from place to place to recover the bodies of victims. 200,000 of them were brought back to the Kigali Genocide Memorial, counted by their skulls as the rest of the bones were mixed together and unidentifiable.

Freddy joined AERG, a group which provided support for student survivors of the genocide. ‘We would come together to cry together, to bring people together to make families for those who had none. It helped us cope.’

In 2004 Freddy was hired by the Aegis Trust to collect testimonies and materials to use in the memorial exhibitions.

I asked him how he and his team, and the country could process such a task at a time so soon after genocide.

‘We were survivors who lost our families, so we saw all these people as our relatives’, Freddy said. ‘We felt that we are here to fill the gap, so that they are not left in shallow graves – so they can rest in peace in a dignified space.’

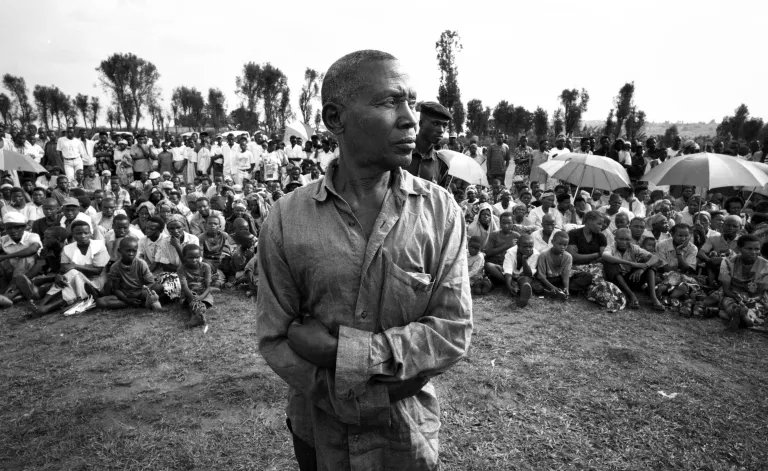

In the years following genocide, some of the main perpetrators were imprisoned, but there were still thousands of people who took part in the killing across Rwanda who still lived among survivors. The government decided to set up Gacaca (meaning grass) courts, where communities tried perpetrators themselves using locally-chosen judges to establish what happened and to decide their fate. It was described by the president at the time as ‘an African solution to African problems.’

A Gacaca court session in October 2001, where local witnesses and judges decided the fate of those accused of crimes during the genocide October 2001 (Photo: MARCO LONGARI/AFP via Getty Images)

Reconciliation

Today, Rwandans who were persecuted, and those who took part in the genocide live together in an extraordinary example of reconciliation.

But immediately after the genocide, the first priority for the new government was to ensure people felt safe and secure. Survivors were left worried that perpetrators would come back to kill them, while perpetrators feared revenge. Many wondered if these tensions could spark up again.

For years after the genocide, Jeanne tells me how her ex-husband – a Nyamurenge (predominantly Tutsi) soldier, would berate her during their marriage, demanding that she admit if she was a Hutu or Tutsi. ‘What are you?!’ he would scream at her.

The government addressed the concerns of security by insisting on a national primary identity of Rwandan first, encouraging people to stop referring to each other as Hutu and Tutsi to further national unity.

Years later, aware that the advice had led to a fear of using the terms or even discussing genocide, the program ‘ndi umunyarwanda’ (I am Rwandan) was launched, encouraging Rwandans to speak about their experiences.

But many still keep these conversations close to their chest. One man requested that we leave the public place we were in before discussing the terms Hutu and Tutsi, fearful for how others around us might react if they overheard.

Reconciliation is complicated, and Beatha says there is a Western perspective on Rwanda’s success which simplifies it.

She said: ‘I don’t like the expression ‘living side by side’, it romanticises us, and assumes we survivors have forgotten what happened. I have forgiven, but I haven’t forgotten. How could I? When I met the man who murdered my mother and asked him why he did it, he responded saying ‘because I was told to’. What am I meant to do with that?’

‘As victims and survivors we have to move on with our lives. Reconciliation requires dedication and willingness, and it was the only option for Rwanda after the genocide, as it still is today. If I wanted to hate all the perpetrators, I would hate my entire village, I would live my life in pain and grief.’

‘But am I healed? In some ways, in others of course not. My children have grown up not knowing their grandmother. I don’t even have a picture of her.’

A country for all Rwandans

The Genocide Memorial has also been key to the reconciliation process. Since 2009, the Aegis Trust has run peace educational programs across Rwanda to ensure that all communities learn about the causes of the genocide. They run mobile exhibitions, work with community leaders and, as of 2014, has had its work implemented into the national education curriculum, reaching 2.5 million children a year.

The powerful Genocide Memorial Centre in Kigali (Picture: SIMON MAINA/AFP via Getty Images)

‘We wanted to ensure that this memorial was accessible to everyone, to survivors, and to all Rwandans. This memorial does not accuse people. It accuses the ideology that leads to genocide’, Freddy says.

I tell him about a conversation I had with a man called Samson the day before.Samson attended a boarding school for orphans shortly after the genocide and told me how a boy sleeping above him had started to scream in his sleep. Samson was confused as the boy was Hutu, but he was told later that the boy was remembering images of his own father hacking down his childhood friends.

Freddy closes his eyes in pain. He says that it is an example why it is important to understand that all Rwandans – even the families of perpetrators – are traumatised. ‘That is why the memorial has to serve them too.’

He adds: ‘There is a lot of change that we needed to make for this country to become what it is like today.’

Rwanda is known as the ‘land of a thousand hills’ (Picture: Edwin Remsberg / VWPics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Every year on April 7th, Rwandans commemorate the genocide of 1994 (Picture: Yasuyoshi CHIBA / AFP via Getty Images)

In the busy Kigali region of Gikondo today, an example of these changes can be seen. Talking Through Art is one of many initiatives which have sprung up in the past few years that aims to bring dignity to the lives of struggling Rwandans, focusing on women with disabilities, teaching them skills to create art that they can sell. It is here that I meet Jeanne. Jeanne is a quiet woman with a wide, infectious smile, proudly posing for my photograph with her latest creation – a huge mat with a giraffe weaved into its centre.

She said: ‘I thank God that I found this place, it’s somewhere where we can come together as a community. I wanted to be an artist as a child you know? It took many, many years but here I am.’

Jeanne Mukankuranga, a survivor, proudly displays her work (Picture: Jeremy Ullmann)

Rwandans are a proud people who do not wish to lose the respect of others, and always look to not make a conversation uncomfortable for guests. As a white person entering these spaces, you could easily assume (based on their absence) that conversations about genocide are not being had, that people have opted to forget it to pursue a better future.

But it is not the case. In spaces such as Talking Through Art, in spaces where people feel safe, it is being discussed.

‘Sometimes we have these conversations together.’ Jeanne says. ‘By doing so we bring back to our minds the images of what happened to us, how it was in those moments. I go home after and I remember the bodies, the image of my brother stabbed in the side with a machete. It makes me cry.’

Rwanda’s own achievement

Freddy says that the Aegis Trust is planning on building what he calls ‘a museum of the future’, a space to celebrate and reflect on Rwanda’s growth, how far it has come, and how it has learnt the lessons of genocide.

‘We’re living in a world of conflict, but we want to show the world that peace is possible.’

Jean-Bosco Gakwenzire (back), 65, embraces his old school friend, Pascal Shyirahwamaboko (R), 68. Pascal was among the killers of Jean-Bosco’s father at Mutete during the genocide. He was tried in a Gacaca court and owned up to his crimes and gradually forged a reconciliation with his one-time childhood friend. (Picture: JACQUES NKINZINGABO/AFP via Getty Images).

And that peace, Bertha is keen to stress, is Rwanda’s own achievement. ‘The West planted the seeds of genocide during colonisation, and they stood by when the genocide happened. 30 years later, perpetrators are still living free, comfortable lives in the West.

‘We achieved justice and reconciliation ourselves. We had help, but if we had asked the West to lead reconciliation, we would still be a divided country.’

‘Rwanda is a country that has risen from the ashes. We might still be processing our past, but we have recovered a great deal because of the resilience and commitment of ordinary Rwandans.’

‘Rwanda is a country that has risen from the ashes.’ (Picture: Beatha Uwazaninka)

Rwanda is an extraordinary place, because of and despite it’s horrific recent history. Its people are determined to build better, for themselves, for their communities, and for their loved ones who perished in the rainy season of ‘94.

Increasing tensions in the Congo involving the Rwandan military and genocide revisionists thriving on social media are reminders that peace and progress are delicate things, but few could look at Rwanda today – Rwanda with its natural beauty, its astonishing economic growth and a national identity that attempts to unify people from all different backgrounds – and not marvel at how far it has come.

There is a line in the Memorial that speaks to the vision that Freddy sees for Rwanda, not just for itself, but for what it could mean for the rest of the world:

If peace and reconciliation are achievable after genocide, they are achievable anywhere.